From time to time, IDRS will choose to make certain articles on the IDRS website available to readers without subscription. This will be done in cases where an article stands to serve a public demonstrably broader than that which would have cause to be regular members of the Society. Decisions concerning the posting (and removal) of such articles will be at the discretion of the IDRS Print Editors in consultation with the IDRS President and Digital Marketing and Communications Coordinator.

Explore Excerpts from The Double Reed

A Timbral Approach to Overlooked Oboe Works by Women Composers: Vivian Fine and Ruth Gipps

by Hilary Hobbs, Grove City, OH, USA

“Through college degree programs, music students become familiar with traditional approaches to musical analysis, and the standard Western art music repertoire by white, male composers. Although essential to understand, solely focusing on theory and musicology for “traditional” composers ignores a wealth of valuable repertoire written by female and BIPOC composers. This lack of representation leads scholars to operate with an incomplete view of the full corpus of existing music.”

Breaking Barriers for American Band Directors and Bassoonists

An update on the Spanish oboist-composer virtuosi Juan, Manuel, and José Pla

Matthew Haakenson Wayne, Nebraska

While the Bassoon Origins Survey detailed in the previous article (The Double Reed, 47/3)

was intended to identify trends in access issues for students, the Band Director Survey described here was created to identify trends in bassoon access issues for both band directors and their schools, and to better understand how band directors recruit, retain, and nurture their bassoonists. The survey was distributed electronically in April 2021 via email and social media with only one qualification: the band director taking the survey must have taught in the United States in public schools at some point. Responses were accepted regardless of whether or not a teacher’s school had access to a bassoon or had bassoon students in their program and did not restrict participation based on band directors’ age, experience, or retirement status.

Continue Reading

O Brother, Where Art Thou?

An update on the Spanish oboist-composer virtuosi Juan, Manuel, and José Pla

Matthew Haakenson

Wayne, Nebraska

Anyone who has engaged in scholarly research knows the process often involves a myriad of difficulties, inconsistencies in information, and, at times, dead ends. In fact, not only does research occasionally yield misinformation and lead scholars far afield, it also never guarantees results. A cursory search for “Pla” in most search engines today, for instance, invariably returns numerous findings related to polylactic acid and the People’s Liberation Army (or PLA) of China. And even when a promising source on eighteenth-century Spanish music is identified, a search for “Pla” within the document typically results in the immediate location of all words containing the letters P-L-A, regardless of where the letters appear in the word, but rarely locates instances of the surname for the eighteenth-century Spanish oboist-composers Juan, Manuel, and José.

Continue Reading

Breaking Barriers for American Band Directors and Bassoonists

Part 2: Bassoon Origins Survey

Ariel Detwiler

Bloomington, Minnesota

The article appearing below is a modified version of the second part of the author’s 2023 University of Minnesota doctoral thesis. The first part of this important work was published in our previous journal (DR Vol. 47, No. 2) and the third part, including data from a survey of band directors’ inclusion of the bassoon in their ensembles, will be printed in an upcoming edition of The Double Reed.

Breaking Barriers for American Band Directors and Bassoonists

Part 1: Introduction and Review of Past Research

Ariel Detwiler

Bloomington, Minnesota

The article appearing below is a modified version of the first sections of the author’s 2023 University of Minnesota doctoral thesis. The second and third portions of this important work, including data from the author’s survey of when and how bassoonists got their starts, as well as a survey of band directors’ inclusion of the bassoon in their ensembles, will be printed in upcoming editions of The Double Reed.

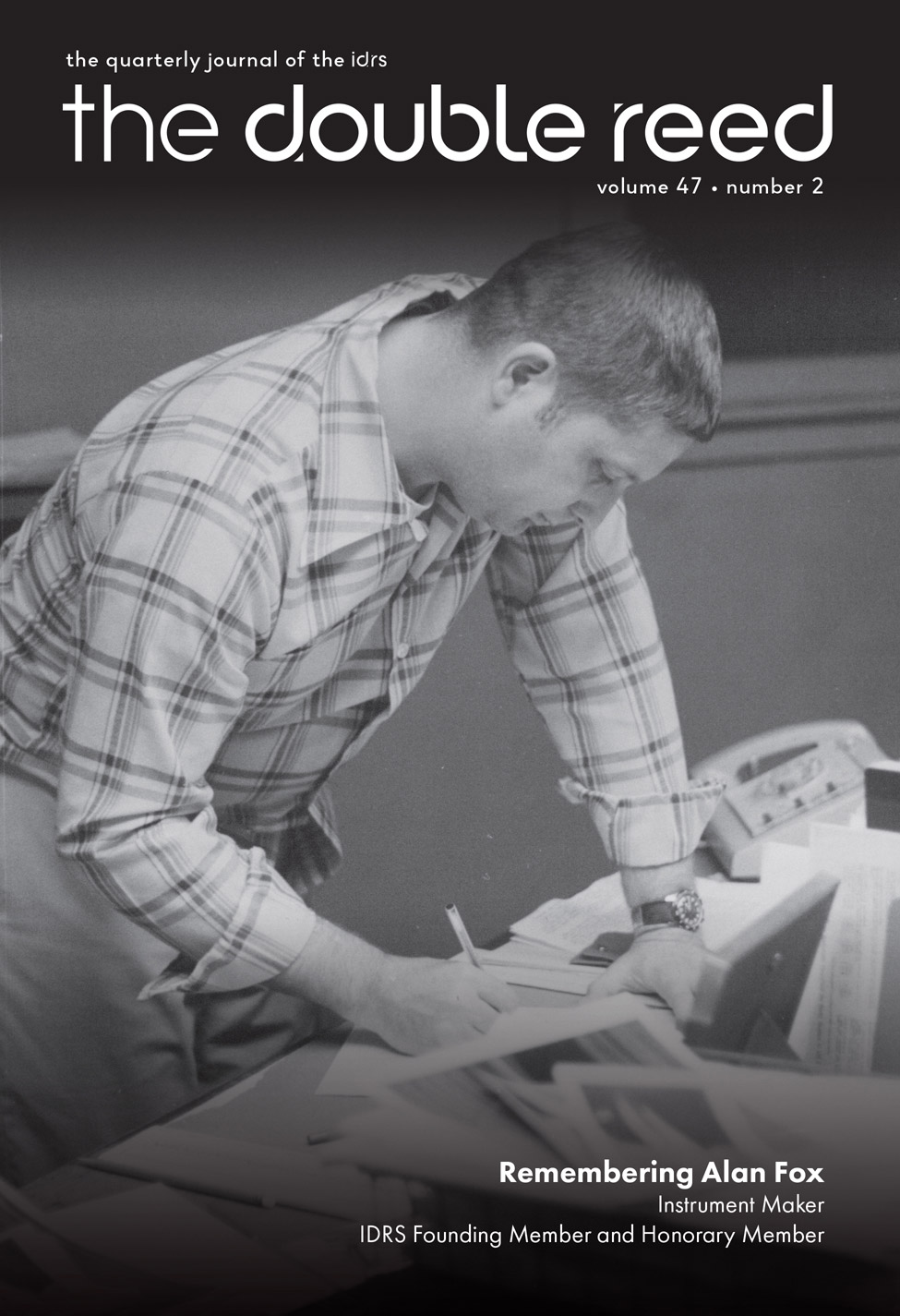

Maurice Bourgue (1939–2023):

Philosopher of the Oboe

Compiled by the Oboe Editor with the generous assistance of

Ombeline Challeat, editor of La Lettre du hautboïste, published by

our affiliate organization, the Association Française du Hautbois

The French oboist Maurice Bourgue died on October 6, 2023 at the age of 83. His reputation as a virtuoso oboist and inspirational master teacher earned him an international following and he performed as a soloist with some of the world’s most distinguished orchestras. Bourgue was born in Avignon on November 6, 1939. His father was an amateur clarinetist, a talent that had helped him to get special treatment when he was a prisoner of war in Germany. He wanted to achieve similar opportunities for his son, and assigned him to solfège classes from age seven, and let him choose an instrument two years later. The boy heard the oboe on radio and was immediately attracted to what he later described as its “solar radiance.”

Jacqueline Piatigorsky’s Bassoon

Bradley Bailey (Saint Louis, Missouri)

It might be exceptional for a story about the significance of music in the lives of the famed couple Gregor and Jacqueline Piatigorsky to concentrate not on world-famous concert cellist Gregor, but on Jacqueline, one of the top female chess players in the United States in the late 1950s and 1960s, whose activities as a musician remain largely unknown, even to her admirers. Yet her occasional musical undertakings provide further insight into the unique nature of the relationship between Gregor and Jacqueline, a singularly talented and philanthropic partnership. Indeed, one of the least known—yet deeply meaningful—signifiers of their storied union remains, of all things, a bassoon, which is currently featured along with several other items from the family archive in the exhibition Sound Moves: Where Music Meets Chess, on view at the World Chess Hall of Fame in St. Louis through January 28, 2024.

Putting a Name to the Face — Warts and All

Geoffrey Burgess (Philadelphia, PA, USA)

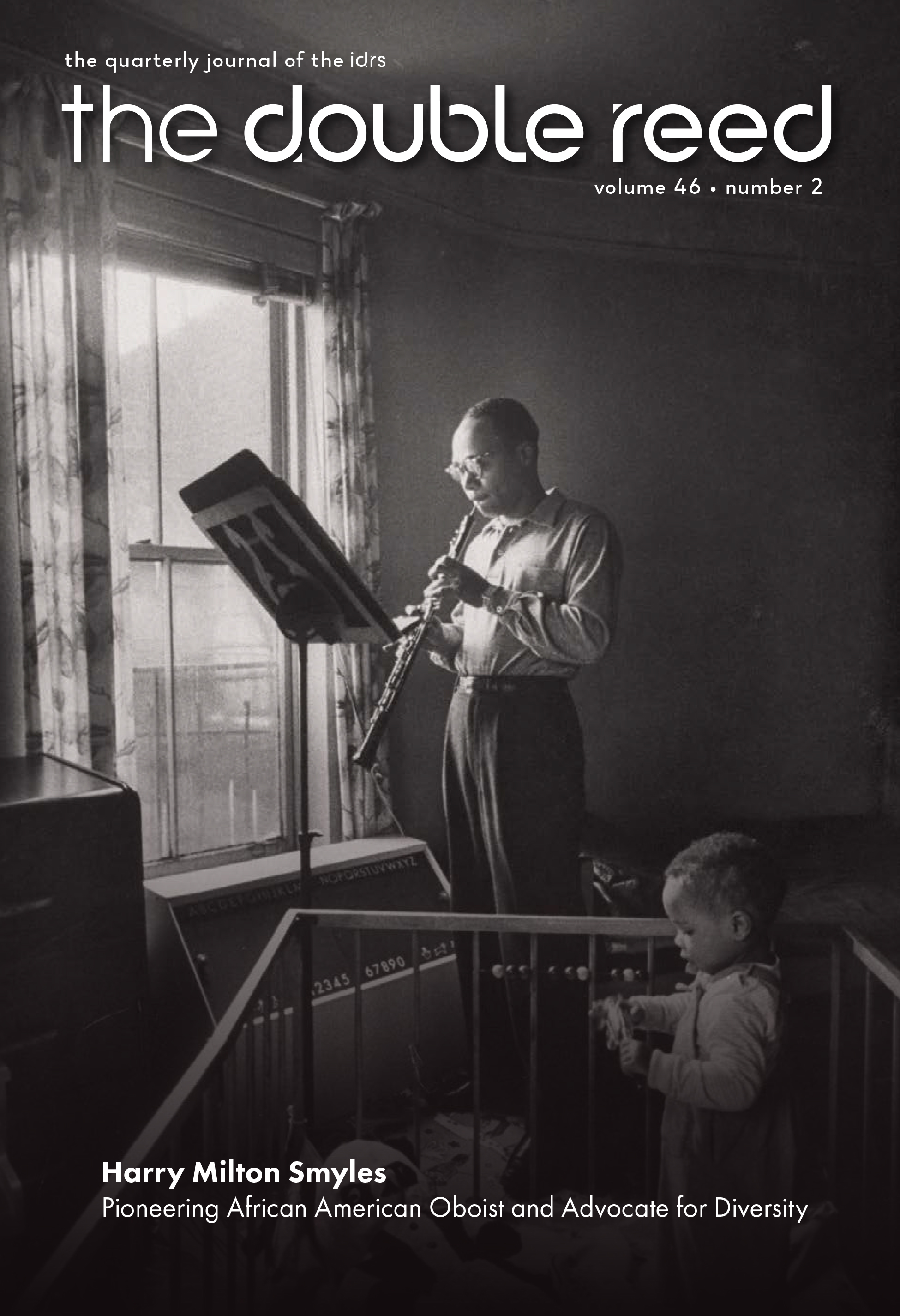

Harry Milton Smyles: Pioneering African American Oboist and Advocate for Diversity

William Wielgus (Alexandria, VA)

Pi Nai – The only reed instrument that most Thai people would at least have heard of.

Capt. Somnuek Saeng-arun (Bangkok, Thailand)

Pi is an ancient Thai instrument that is believed to originate from the reed pipes called re-rai or pi re-rai played by folk people. Another ancient form of this instrument is the pi nam-tao, constructed by means of inserting a bamboo tube called pai-sang (Dendrocalamus strictus) into a calabash gourd. At some time, hardwood was adapted for the body of the instrument and the dried leaves of the Asian palmyra palm (Borassus flabellifer) came to be used for the reed. This newer kind of pi is used in many forms of ceremonial music. It is the only wind instrument in the Wong Piphat ensemble which is named after it. The Wong (or band) comprises pi, ranad thum (xylophones), gongs, and drums. This is mostly how the pi is heard today.

Yusef Lateef’s Legacy for Oboe Players

Ellen Hummel (Las Vegas, Nevada)

Classical musicians all over the world are challenging the traditional Classical canon, and re-evaluating the music traditionally performed and taught. As part of that process, this article makes a case for oboe players to investigate the legacy of Yusef Lateef (1920–2013), a pioneer of creating music that transcends boundaries, and a musical genius who reimagined the voice of the oboe in a variety of musical settings.

Although Yusef Lateef is primarily remembered as a jazz musician, it is clear from his biography that he was much more than that. Through his studies and travels, as well as his association with other jazz innovators, Lateef expanded his musical language to include everything he came in contact with. Lateef famously disliked the term jazz, and created the term “autophysiopsychic music” to describe his output. This was an all-encompassing global approach to music-making that transcends all genres, and can be heard in his many recordings and is documented in his method books.

The State of the Bassoon in Music Programs Across the U.S.

Dr. Shannon Lowe (Gainesville, Florida)

While teaching at a small regional institution located in the Southeast, I struggled with recruiting bassoonists. I sent out fliers, emails, posted YouTube videos of all-state etudes, and co-hosted numerous double reed days. No matter what I tried or what events I scheduled, I always encountered poor showings of student bassoonists. While visiting middle and high schools to work with and recruit bassoonists for my program, in most cases, I was met with an ensemble director saying “Well, we do not have any bassoonists in our program,” or “Since we do not have any bassoons to give out, I cannot start any students on the instrument .” It was indeed disheartening and led me to wonder what the root cause of this lack of bassoonists was. I contemplated my own beginnings on the instrument . After all, I had no idea what the bassoon was when I chose it. All I knew, as a sixth grader excited for band, was that I wanted to play something different. I asked my band director if I could play the English horn, and he said that the program did not own one. He offered oboe or bassoon to me. I chose the bassoon because the name sounded cool. That day, he handed me the case with a beginning band book and said “Here you go. I have no idea how to teach this. You are on your own .” The instrument I received was in poor condition and beat up from years of neglect. With no guided instruction in the first stages of learning the bassoon, I was really left to figure it out on my own.

Conductors and Orchestras

John Steinmetz (Altadena, California)

After several decades of orchestral playing, I have come to believe that the power relations between players and conductors often prevent orchestras from reaching their potential. Conductors have too much power, and that power too often hampers players, orchestra organizations, and conductors themselves. The culture of communication in orchestras tends to allow musical and interpersonal problems to fester. To make matters worse, conductors generally receive little or no supervision; their superiors are non-musicians who cannot assess a conductor’s effectiveness.

Despite investing considerable energy in coping with these problems, orchestras don’t discuss them much. I want to encourage discussion so that orchestras can search for solutions. My purpose here is to stimulate conversation.

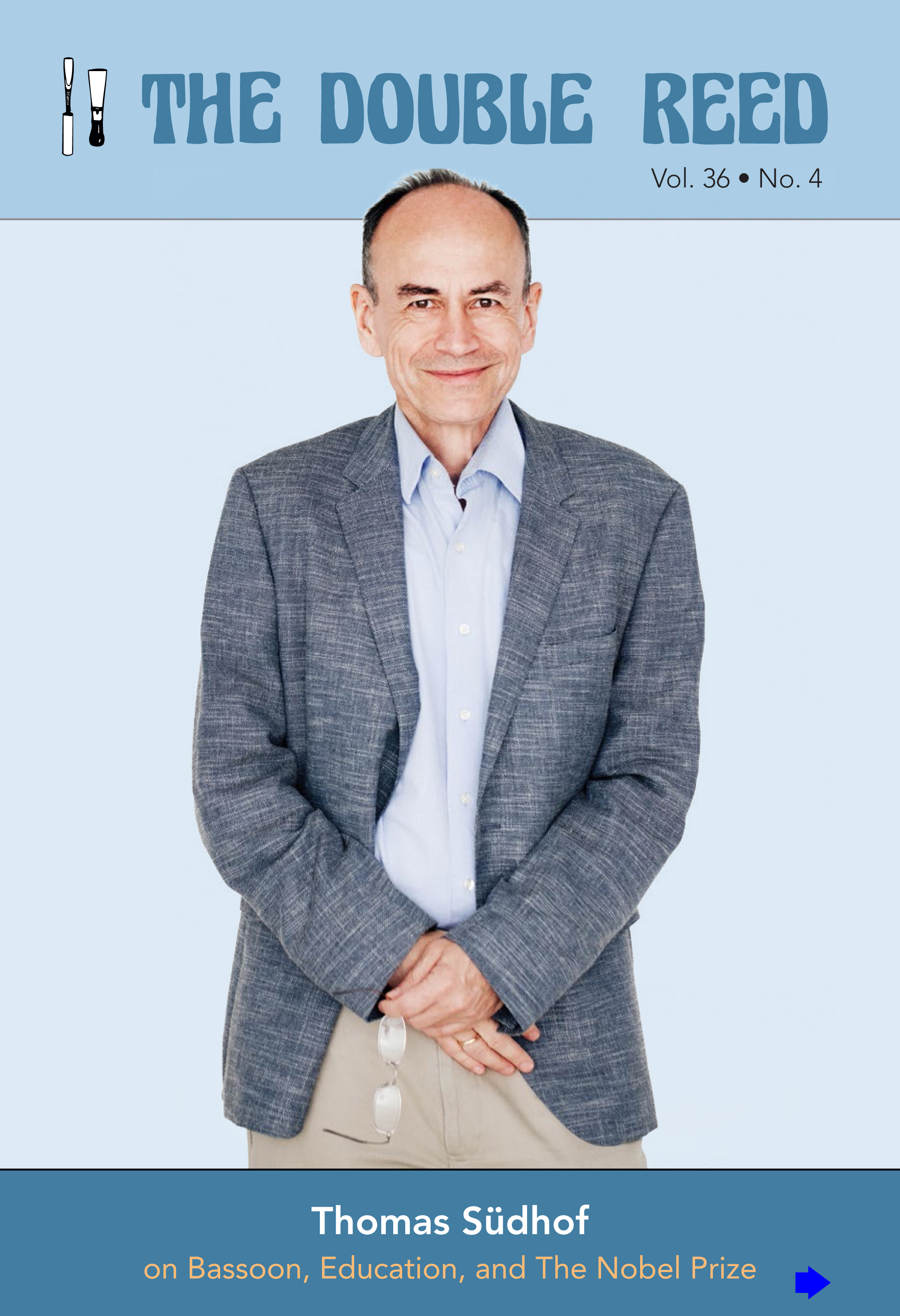

From Bassoonist to Nobel Laureate: An Interview with Thomas Südhof

Ryan D. Romine (Winchester, Virginia)

In October of 2013, neuroscientist Thomas Südhof was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on explaining the mechanisms of the presynaptic neuron. This research, exploring what happens when the presynaptic mechanism works correctly as well as when it malfunctions, gives us a much deeper view into how the healthy brain relays information and how conditions such as autism and Alzheimer’s disrupt that relay process.

But what does this have to do with double reeds? In a fantastic set of coincidences mirroring 2013’s Nobel win in Physiology or Medicine (see our interview with Dr. Thomas Südhof in The Double Reed Vol. 36, no. 4), one of the 2014 laureates, William E. Moerner, is also a professor at Stanford University AND once played the bassoon! Might there be a connection between the school, the instrument, and the prize? Only time will tell. But, in the meantime, Dr. Moerner has very kindly agreed to share a few thoughts with our readers.